In November 2024, Boxer listed on the JSE. Pick n Pay still holds a controlling stake, but the retailer has now been set free to prove itself as a separate listed company, and to shore-up its parent’s share price.

As a limited-range, discount grocery retailer, spending at Boxer is supported by the benefits that certain customers receive from South Africa’s social grant system. The pre-listing statement goes into great detail about the importance of social grants to grocery spending among lower-income households, and the reader may therefore infer that Boxer will benefit disproportionately from the expected resilience and expansion of the social grant system, as it executes the key element of its own strategy: grow its store network.

Slant is typically sceptical about the window-dressing that accompanies new listings; part of our mission is to validate the rose-tinted declarations that companies often make, knowing that investors typically lack the information to validate such declarations.

So, we looked at the data: actual spending by real consumers.

Social grant recipients spend 12% more on groceries…

We analysed thousands of anonymised bank statements from consumers in the target demographic and isolated 3,144 individuals who received at least one social grant payment between April and June last year. While the social grant payment averaged just R307, these individuals received an average total income of R4,330 each month.

Then we reviewed all spending at identifiable grocery outlets. On average, our sample spent R743 at these retailers during the period.

For a comparison, we identified a control sample of customers in the same income bracket, but these individuals did not receive a social grant payment during the period.

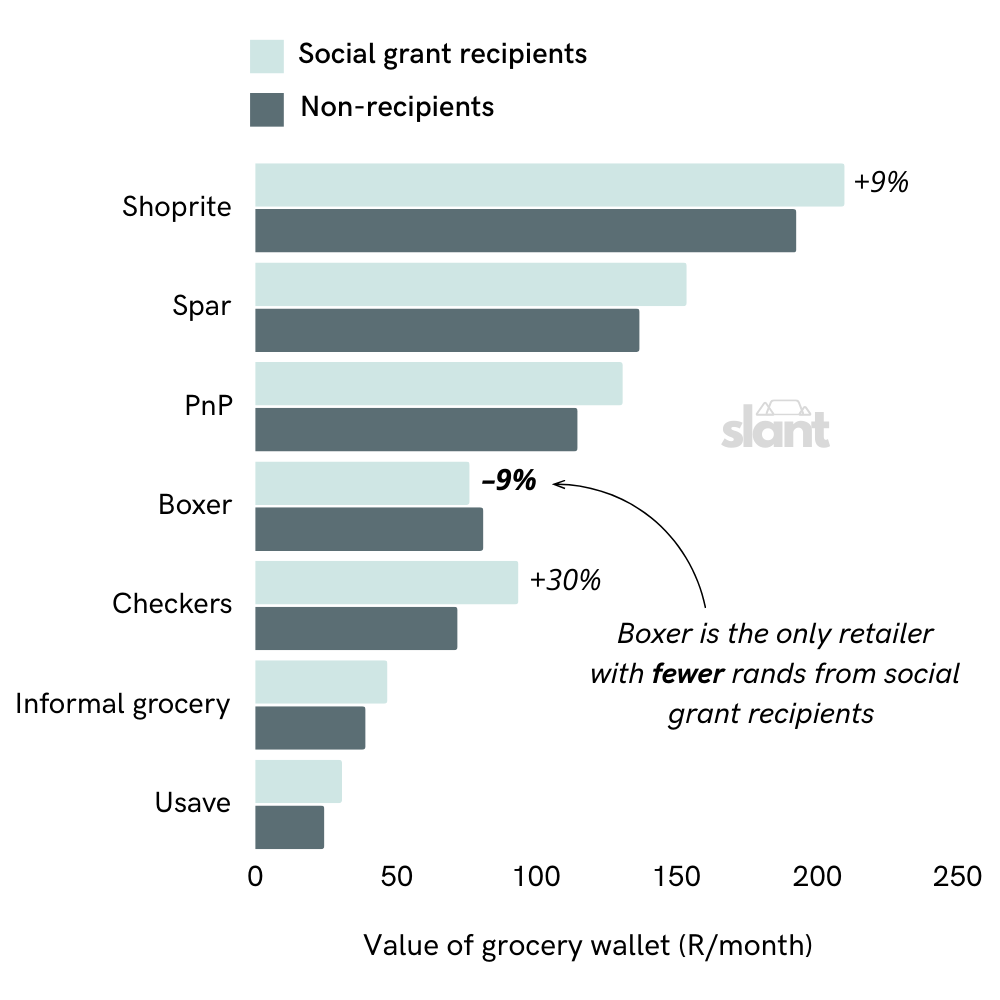

Based on this analysis, it’s true that customers who receive a social grant spend more on groceries. (Shoppers in the control sample spent R662 on groceries: 12% less than the social grant recipients.) This lends credence to the idea that people who receive a grant spend more at mainstream grocery retailers than people who do not receive a grant.

…but they spend less at Boxer than non-grant recipients do

When we break down spending by retailer among the cohort of consumers receiving grants, and compare that spending to the consumers who do not receive grants, spending is greater in absolute terms at all retailers, with one exception: Boxer. People who receive social grants spend less at Boxer than those who do not.

In other words, for the group of consumers represented in our data, those who receive a social grant may in fact prefer to shop for groceries at a supermarket with a wider range and selection, not just at the lowest-price store in town.

What does this mean?

At the end of the day, social grants offer a significant safety net to millions of people, and they’re an important feature of the local retail landscape. But the real impact of grants remains opaque to most analysts. That’s where alternative data comes in. The transaction data we’ve used here, for example, offers a glimpse into the real spending choices and behaviour of an often-misunderstood demographic group.

Of course, our findings do not undermine Boxer’s growth strategy, which seems credible and well-rounded. The real value of this analysis is that it sense-checks management claims that sound impressive but are almost impossible to measure, thereby giving analysts a better understanding of the companies they may be investing in.